Updated: March 16, 2024

The customer pounds his fists on the counter.

He bellows with rage, spittle flying out of his mouth like angry rain. “This is your fault! You screwed up! You need to fix this!”

The customer’s tirade feels like an attack. He means the company when he says “you,” but it feels personal.

“Don’t take it personally,” is awful advice.

That’s the most common tip for serving an upset customer. But it doesn’t work. Taking it personally is a natural reaction.

Here’s what to do instead.

Why don’t take it personally is bad advice

Your defense mechanisms automatically kick in when confronted with a physical or psychological threat. You instinctively fight off the threat or flee it.

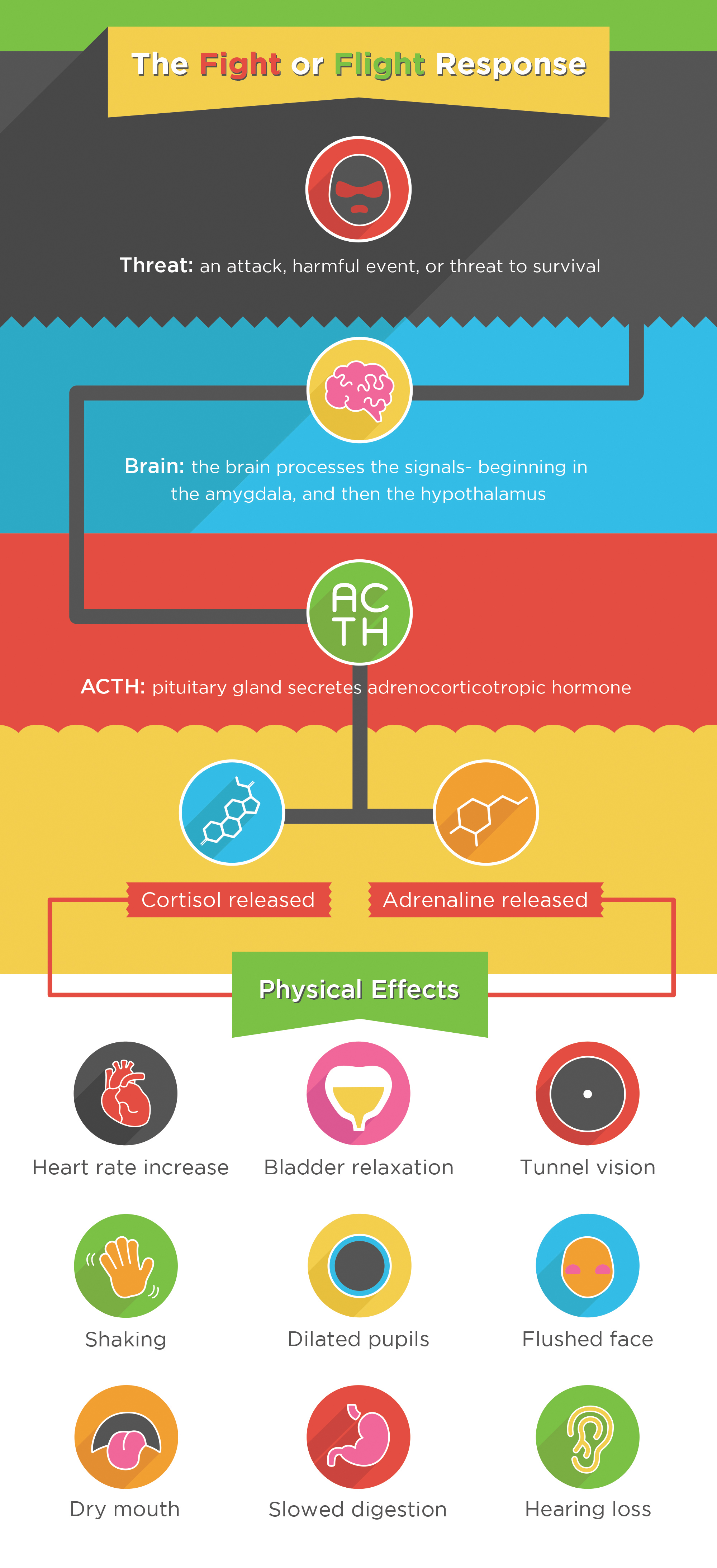

This instinct is called the fight or flight response. It helps in many situations.

For example, let’s say you’re accosted by a growling, snarling dog. There’s no time to plan your reaction. You instinctively confront the dog or try to get away.

Customer service is one place where this instinct doesn’t serve us well.

Try to imagine that furious customer. He’s pounding his fists on the counter and yelling. Taking it personally is a natural reaction.

Your instinct is to either confront the furious customer or try to get away.

What triggers the fight or flight response?

An angry or upset customer can trigger your instinctive flight or flight response. Here are a few examples:

Yelling at you

Making derisive comments about you or your company.

Accusing you or your company of wrongdoing.

The infographic below illustrations our physiological reactions to a “fight or flight” situation.

Source: Jvnkfood

How to overcome the fight or flight response

Recognize that the fight or flight response is a powerful instinct. Pithy advice like “don’t take it personally” isn’t enough to handle it.

I have two suggestions for overcoming this challenge:

Identify your triggers. Try to be aware of what triggers your fight or flight instinct. Recognize the instinct as it starts to happen.

Pause. Catch the instinct before it takes over. Pause and make a better decision.

This short video from my Working with Upset Customers course shows you an example. You’ll see two scenarios from a coffee shop.

Scenario 1 is at 1:25. Here, the coffee shop barista does a poor job controlling his fight or flight response.

Scenario 2 is at 2:56. This time, the barista identifies the fight or flight response kicking in and takes a brief pause.

Training your team to serve upset customers

Serving upset customers is difficult. Your employees need training, coaching, and practice to develop these skills.

Here’s an exercise you can use to train your team on the fight or flight response:

Show your team the recognizing your natural instincts video.

Ask them to identify their own “fight or flight” triggers.

Have your team practice becoming aware of this response while serving customers.

You can use these resources to provide even more training: